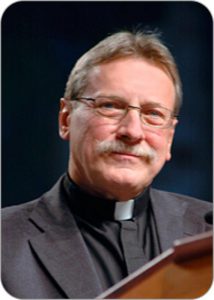

FROM THE PASTOR

Yolanda’s Story

AAMPARO is the ministry of the ELCA which accompanies migrant minors (and their families) in Central America, their country of origin (especially the Northern Triangle: Honduras, Guatamala and El Salvador); in Mexico (the country of transit); and at the southern border of the US. I was Director of Domestic Mission for the ELCA and Rafael Malpica-Padilla was Director for Global Mission. We led a delegation to Central America to hear the stories of those who have been deported, and to hear what drives families to attempt to migrate to the US. This is one of the stories we heard:

San Pedro Sula, Honduras We enter a tiny home—bare, stark, without plumbing—and met Yolanda (we have changed her name for her protection) and her children. One son, about five or six, curls on her lap. With them are her two daughters, nine and eleven, and a cousin, ten. We are in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, the second-most violent city in the world. Yolanda has just been deported from Mexico with three of her children after trying to reach the United States. She left because her life and that of her children had become untenable. She is in her forties, well educated, but had lost her job. She could not find another one, because unemployment has skyrocketed in their economy, so she could no longer feed her children. The culture of violence in Honduras is stark and pitiless. Yolanda’s older son Emilio was walking down the road with a girl when gang members walked up and killed her right in front of him. He was then caught between police, who wanted his testimony, and the Mara gang, who demanded his silence. The gang threatened her son and then began to recruit her daughters. To resist this recruiting is often a death warrant.

She paid the coyotes, who expedite illegal immigration to the United States, $6,000, exhausting her life savings and borrowing heavily from family. The coyotes told the comforting lie: “This will be easy.” They went through Guatemala and into Mexico, walking for many days. The thirst, the heat (“Muy calor!” her son chimed in, sitting on her lap). They were kidnapped by the Gulf Cartel, aided by her coyote. They tied her son by his hands and feet. “Don’t do that to my child!” Yolanda yelled at them. “Do you want to get shot? Shut up.” They then gave her son cigarettes and let him hold a gun. The kidnappers were between eighteen and twenty and apparently high on drugs. They sexually violated some of the other women they held hostage. Yolanda made her children leave the room when she described this to us. The violence and terror were constant. The kidnappers would put guns in people’s faces, kick people. Yolanda and her children were held in a house in Tampico for a ransom—equivalent to $3,000 each. So many migrants interdicted in Mexico are commodified and become victims of traffickers. Some talked about hiding in a cave, about seeing cadavers left over from human organ trafficking.

Now Yolanda’s telling of the tale escalated and she spoke rapidly. They escaped. A guard put his gun behind the sofa, and the captive men rushed him and his associates while the leader was out. Yolanda was upstairs. Some in the group jumped from the window. She and her children were at a window when some of the men who had escaped came back for them. She dropped two of the children out the window to rescuers waiting below. She and the other children jumped down, and they all ran barefoot toward safety. They hid in a drugstore. The local police came, but Yolanda recognized them, remembering they had brought pizzas to the kidnappers. The store owners hid them.

Finally, immigration police came and took them into custody. The detention in Tampico was bad, but Tapachula, in the state of Chiapas, was the worst, as Yolanda describes: “Horrible. Dirty mattresses. Smelly. Only one lousy meal a day.” A human warehouse, devoid of humanity. Yolanda somehow found the courage to stand up for those being abused, especially Guatemalans who spoke an indigenous language and could not speak Spanish. “We are human beings, treat us well,” she demanded. After six days there they were deported on a bus, back to the unspeakable violence of San Pedro Sula.

She described her life now: “We are living life on the run. My older son Emilio still lives with us and is still hiding from the gangs. The Mara are all around here. This neighborhood is a dividing line between two gangs. My children are traumatized. They have nightmares. I work as a domestic maid. I make $100 a month, which barely pays rent, electricity, and water.” She has only enough to scrape up one meal a day for her family. It has been four years since she lost her job.

Stories like Yolanda’s would be repeated many times by those willing to share their experiences with us. Poverty, no economic hope, extreme and constant violence pushed children and families to flee, only to embark on a journey replete with violence, exploitation, and abuse. And in the end, they were caught and sent back to the very conditions threatening them in the first place.

And then Yolanda shared her faith. “I am so grateful that my kids are in a Christian school. I am thankful to God that they are okay. I am at home.” Her hand swept across the tiny, humble shack. “I am at peace in my home. I am grateful to Casa Alianza for all their help.” (Counseling, case management, help with books and uniforms for school were the only follow-up Yolanda received after getting off the deportee bus.) “I am more than a sad case,” she says. She shared her incarnation theology: “My kids and I are precious to God. God is right here with us. Scripture says that foxes have holes, birds have nests, but Jesus didn’t have a place to lay his head. He knows I am here; he knows my children. He will not abandon us.” She grasped her Bible. “All books inform us, but the Bible forms us.” She then expressed gratitude for our coming to be with her. She thanked us for listening, a refrain we would hear repeated again and again. Rafael prayed with us all and blessed the home and family. The kids hugged us. Yolanda was in tears—a proud, wise, compassionate sister in Christ. As we left, Michele, her oldest daughter, gave each of us a beautiful card she had made during our visit. The cards were red, with interwoven hearts and expressions of love. It was Valentine’s Day.

Yolanda is now one of our Global Mission leaders in the AMMPARO ministry of accompaniment in San Pedro Sula, working with Casa Alianza, one of our partner programs in San Pedro Sula.

(This story is an excerpt from “They Are Us: Lutherans and Immigration, Second Edition,” by Stephen Bouman and Ralston Deffenbaugh—(the book is in St. Luke’s library)